Two Timelines, One Workplace

Picture two parallel timelines.

In the first, the late 1980s and 1990s unfold with remarkable momentum; the Cold War ends, markets surge, Technology booms. Globalization accelerates. For many who came of age professionally in this era, the prevailing belief was that progress was not only possible—it was probable. Careers tended to advance with time and effort.

Organizations grew. Homeownership felt achievable. Institutions, while imperfect, were generally trusted to function. The future seemed expansive, and optimism was a rational stance.

In the second timeline, the formative years look very different. The earliest memories include 9/11 and its aftermath—geopolitical uncertainty replacing post-Cold War stability. A global financial crisis disrupts families, jobs, and communities. Student debt rises sharply. Wages stagnate for early-career workers. Climate risk becomes a lived reality, not a distant debate. Institutions—from government to media to corporate employers—lose credibility. The pandemic then arrives as a generational bookend, reshaping norms again just as stability seemed possible. For those who entered the workforce in or after the 2000s, volatility is not an exception; it is the baseline. “Hope for the best” is not a strategy, it is a luxury.

These two timelines now sit at the same conference table.

Leaders who experienced the 1990s internalized a world where improvement was the default trajectory. Younger professionals internalized a world shaped by shocks, uncertainty, and eroding guarantees. Neither timeline is “right” or “wrong”—but they create fundamentally different expectations for the future, for institutions, and for what “good leadership” looks like.

This divergence has created what many executives are now experiencing as a cross-generational communication gap in the workplace. It is often misinterpreted as entitlement (“They expect too much too fast”), cynicism (“They’re negative or alarmist”), or complacency (“They don’t see the urgency”). But the truth is simpler and more human: people are drawing conclusions based on the world that formed them.

To lead effectively across generations today, executives must understand the two timelines that shape how their teams perceive risk, progress, trust, and the future. Doing so creates space for connection; built not on nostalgia or critique, but on empathy, evidence, and shared purpose.

The Generational “Optimism Gap.” A Matter of Lived Reality, Not Attitude

Much has been written about generational differences in the workplace. Millennials want purpose. Gen Z values balance and authenticity. Gen X prizes autonomy. Boomers respect tenure and dedication. But beneath those stereotypes lies a deeper divide—a difference in learned expectations about the future.

This difference is often mislabeled as an attitude problem. In reality, it is a rational response to different conditions.

Leaders who grew into their careers in the late 20th century were shaped by a period of sustained expansion. In the U.S., the 1980s and 1990s saw strong GDP growth, a wave of technological innovation that created entire new industries, and comparatively lower living costs relative to wages. Homeownership was more accessible. Corporate ladders were clearer. The implicit social contract—work hard, show loyalty, move up, build wealth—held true for many.

That worldview still informs leadership norms today, especially among senior executives who succeeded in that environment. Optimism is seen as a leadership virtue. Risk is viewed as a lever for gain. Change is navigable because the destination, historically, was improvement. For those whose careers began after 2001, the dominant lesson has been different.

They entered adulthood amid terror attacks, recession, layoffs, rising tuition and debt burdens, and diminished institutional credibility. Their careers began in or were disrupted by the 2008 financial crisis—or were reshaped by the COVID-19 pandemic. Economic mobility became less predictable. Trust in institutions fell. Progress no longer felt guaranteed.

It is not that younger professionals lack optimism—it is that they learned caution.

While older generations were taught by experience that things tend to get better, younger generations were taught that stability can evaporate quickly. A “prove it” mindset replaced a “believe it” mindset.

This is not a clash of values—it is a clash of contexts.

Executives often describe younger teams as “hesitant to commit without certainty,” “overly concerned with sustainability or ethics,” or “skeptical of corporate messaging.” But for many under 40, skepticism is not rebellion—it is self-protection. Optimism, if not grounded in evidence, can feel careless or even unsafe.

Understanding this shift is not about assigning blame. It is about recognizing that leadership messages grounded in 1990s optimism often fail to resonate with teams shaped by volatility. To communicate effectively today, leaders must first acknowledge the validity of multiple lived realities.

What the Research Reveals About Diverging Expectations of Progress

This optimism gap is not anecdotal—it is well-documented across research in economics, sociology, and psychology. Multiple studies over the last decade illustrate that the assumption of generational progress—a cornerstone belief in late-20th-century leadership—has weakened significantly.

One of the most referenced analyses comes from economist Raj Chetty and colleagues, studying what they call the “Fading American Dream.” Their research tracked absolute economic mobility across generations using U.S. tax records. For children born in 1940, over 90% grew up to earn more than their parents. For those born in the 1980s, that number dropped to around 50%. In less than a single working lifetime, the likelihood of surpassing one’s parents financially was effectively cut in half.

This shift alone is enough to alter a generation’s implicit expectations of the future.

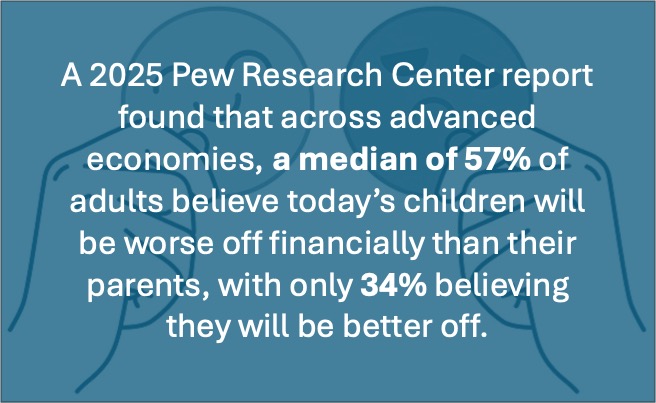

Public sentiment mirrors this trend. A 2025 Pew Research Center report found that across advanced economies, a median of 57% of adults believe today’s children will be worse off financially than their parents, with only 34% believing they will be better off. In the U.S., that share is even more pessimistic. Notably, Pew found few consistent differences by age on this question—meaning it is not only younger people who feel this way. The belief that progress has stalled is widespread.

Gallup polling shows a similar pattern. Optimism that the next generation will enjoy a better life fell sharply after 2019, reaching near record-lows by 2022. What was once a majority belief is now a minority one.

Beyond economics, well-being trends reflect a generational shift as well. Research aggregated by economist David Blanchflower across 11 major U.S. surveys finds that younger adults report declining life satisfaction relative to older adults—a reversal of historical patterns in which younger cohorts were consistently more optimistic.

These data points form a consistent picture: the experience-based belief in upward progress—once a norm—is no longer supported by outcomes.

A second major factor contributes to the divergence: trust.

Trust in institutions has declined across generations, though the impact is more pronounced for those who never experienced a high-trust era. Pew’s long-term analysis of the U.S. General Social Survey shows a steady erosion of social trust—from 46% of Americans agreeing that “most people can be trusted” in the early 1970s to about 30% in recent years. Trust in government has faced an even more dramatic drop.

People who came of age when trust was higher often view institutions as repairable. Those who came of age when trust was already eroding often view institutions as unreliable by design. That belief shapes risk tolerance, loyalty, and expectations of employers.

In other words, the optimism gap is not rooted in personality—it is rooted in structural and statistical reality.

How These Two Timelines Show Up at Work

When people shaped by different timelines work together, they bring contrasting assumptions about progress, risk, communication, and leadership expectations. These differences often surface not as philosophical debates, but as everyday friction in meetings, planning sessions, performance reviews, and change initiatives.

To the executive who internalized the “improvement is the default” worldview, optimism is responsible leadership. It builds confidence, inspires teams, and signals resilience. When markets dip, optimism says: “We’ve been through cycles before—stay the course.”

To younger professionals formed in volatility, optimism without evidence can feel dismissive or unmoored. Their baseline expectation is not that things will naturally get better—it’s that you prepare for the possibility they won’t. When they ask for data, caveats, scenario planning, or transparency, it is not negativity—it is due diligence.

This disconnect quietly shapes workplace dynamics in several ways:

1. Communication Style and Credibility

Executives seasoned in the 1990s learned to lead with vision and confidence. But in a lower-trust environment, messages that rely on reassurance (“We’ll be fine,” “Things always work out,” “This is nothing we haven’t seen before”) can feel unsubstantiated.

Younger employees often look for clarity, transparency, and rationale. They value leaders who show their work: the assumptions, risks, and trade-offs behind decisions. Where senior leaders may see requests for more context as questioning authority, younger employees see it as building trust.

2. Change Tolerance and Risk Appetite

For many Gen X and Boomer leaders, risk-taking paid off historically—companies expanded, markets rewarded bold moves, and the downside felt survivable. Younger talent often experienced or witnessed the opposite: families losing homes in 2008, layoffs without warning, industries disrupted overnight, or career progress stalled by the pandemic. As a result, they may approach change more analytically.

This is not caution without ambition—it is strategic realism shaped by lived outcomes.

3. Career Path Expectations

In the “first timeline,” loyalty and tenure were rewarded. Career ladders were predictable. Today’s younger professionals learned that linear progression is no longer guaranteed. Proactivity, skills diversification, and boundary-setting became necessary for survival. Thus, they seek clarity on growth, development, and equity—not because they are impatient, but because ambiguity has historically turned into vulnerability.

4. Accountability and Transparency

In lower-trust conditions, people crave transparency because it is the only currency that feels safe. They respond not to institutional authority, but to earned trust. Leaders who share context, admit uncertainty, and articulate decision criteria gain credibility. Those who default to “just trust us” lose it.

5. Organizational Purpose and Values

Younger generations experienced institutions breaking their promises—financial, governmental, educational, corporate. As a result, they look for alignment between what organizations say and what they do. Values are not branding—they are due diligence. Leaders who underestimate this shift risk cultural disengagement.

Across all of this, the friction is not rooted in values. Both timelines value progress, stability, fairness, growth, and meaningful work. The difference lies in how each learned progress happens and what signals prove it.

Understanding this is the doorway to bridging the gap.

A Leadership Playbook for Bridging the Two Timelines

Executives today are not just managing functions and delivering results—they are reconciling two lived histories of how the world works. The most effective leaders are developing a new leadership language that honors both optimism and realism.

Below is a practical playbook that executives can implement immediately to foster cross-generational trust, communication, and alignment.

1. Acknowledge Both Realities Explicitly

Statements like “I see why this might feel uncertain” or “For some of us, downturns were temporary; for others, they had lasting impact” demonstrate awareness. Acknowledgment is not agreement with pessimism—it is validation of lived experience. This simple act reduces defensiveness across generations.

2. Pair Optimism with Evidence

Reframe “We’ll be fine” into “Here is why we believe we can succeed, and what indicators we’re watching to validate our path.”

This approach allows optimism to remain a leadership strength, grounded in credibility.

3. Communicate in Dual Timelines

When announcing initiatives, strategies, or change, address both worldviews:

For the 1990s-formed mindset: emphasize opportunity, adaptability, long-term vision.

For the post-2000 mindset: outline risks, mitigations, contingencies, and early warning signals.

This “dual language” meets both psychological baselines.

4. Replace Assumptions with Transparency

Commit to explaining why decisions are made, not just what will happen. Share assumptions, data sources, alternatives considered, and criteria for success. Transparency is no longer a bonus—it is a leadership requirement.

5. Show Progress in Smaller Increments

Annual goals and five-year plans feel long and abstract in a volatile reality. Incorporating short-term wins, milestone check-ins, and visible measures of progress helps both timelines stay engaged—optimists see momentum; realists see proof.

6. Create Mobility Pathways That Reflect Today’s Reality

Earning advancement is still important—but the ladder is gone. Replace opaque or time-based promotion models with:

Skill-based progression

Clear criteria for advancement

Project-based leadership opportunities

Manager support for development

This preserves meritocracy while adapting to the modern landscape.

7. Build Trust Through Consistency and Follow-Through

Trust is no longer granted by role or institution—it is earned through behavior.

Leaders build trust today through:

Doing what they say they will do

Communicating when circumstances change

Addressing issues transparently

Modeling the values the organization claims

8. Invite Multi-Generational Co-Creation

Don’t just “manage” the generational dynamic—harness it.

Create mixed-generation working groups to co-design strategy, operations improvements, culture initiatives, and customer experience. Each timeline contains strengths the other benefits from:

Experience + perspective

Innovation + adaptation

Optimism + realism

Confidence + vigilance

Together, they form strategic resilience.

Closing the Gap — A Shared Future Built on Understanding

The workplace has never contained more simultaneous generational experiences than it does today. For the first time in modern history, five generations may share the same organization. But it is the two dominant timelines—the “upward momentum era” and the “volatility era”—that shape the deepest communication divide.

This divide is not a barrier to progress. It is an opportunity for leaders to evolve.

Executives who recognize these divergent realities and adjust their leadership approach will unlock stronger alignment, higher engagement, and more resilient performance. They will cultivate cultures where optimism and realism are not competing ideologies, but complementary strengths.

Ultimately, bridging generations at work is not about changing minds—it is about widening understanding. The future will require leaders who can hold multiple truths at once, communicate with transparency and empathy, and build trust that withstands uncertainty.

Progress is no longer a guarantee. But with awareness, adaptability, and intentional leadership, progress can once again become a shared endeavor.

We do not need one timeline to “win.”

We need to honor both—and build the future together.

About The Weiwood Group

The Weiwood Group is a leadership and operational advisory firm that helps organizations turn strategy into momentum. We specialize in aligning people, process, and performance to build workplaces where clarity, trust, and accountability thrive. Through practical frameworks and empathetic leadership coaching, we help executives create cultures that evolve with today’s workforce — and deliver results that last.

Ready to strengthen alignment across your organization?

Weiwood Group partners with executive teams to clarify strategy, elevate leadership communication, and build trust across every level of the workforce. If you’d like a conversation about how to bridge generational mindsets inside your organization, we’d be happy to connect.

Schedule a conversation:

👉 https://weiwoodgroup.com/contact/

JD Woods is the founder of The Weiwood Group, a leadership and operational advisory firm.

He helps executives align strategy, culture, and communication to build high-trust, high-performance organizations across generations.